Nihon Eiga: The History of Japanese Film

From the NFAJ Non-film Collection

●Closed when the temporary exhibition is closed.

- Location

- Gallery (7th floor)

- Hours

- 11:00am-6:30pm (admission until 6:00pm)

*Last Friday of every month: 11:00am-8:00pm (admission until 7:30pm) - Closed

- Mondays, Temporary Exhibition installation periods, Year-end and New Year holidays.

- Admission

- Single Ticket 250 (group admission 200) / University & College Students 130 (group admission 60)

*Free for Seniors (age 65 or over), High School Students and under 18; Persons with disability and one person accompanying each of them are admitted free or charge.

*By showing NFAJ’s screening ticket or purchase confirmation email for online ticket, Group Admission fee will be applied.

For more detailed information, please see the following page (in Japanese).

Click here for Chinese.

Click here for Korean.

Japanese cinema has already had a history of over one century with two golden ages. Targeted towards diverse generations of viewers ranging from elementary school students to adults, this exhibition will survey the history through posters, still photographs, devices and equipments for filmmaking, and the personal items that belonged to noted film personalities, among others from the NFAJ Collection.

*Captions in Japanese, English, Chinese and Korean

The Birth of Japanese Film: from the Pre-Cinema Period to the 1910s

During the Edo era (in 1803) Toraku Kameya modified the magic lantern imported from Holland, and ran a show called “Utsushie”.Called “Nishiki Kagee” in the west,“Utsushie” spread all over Japan. The style of the show was mixed with noisemakers such as shamisen or drums, and traditional singing like “Joruri” or “Gidayu”. The relation of visual media and verbal technique led to the later existence of the “Benshi”,peculiar to Japanese film. In the Meiji era (1868-1912), with the objective of propagating the new ideas from the occident, the “western magic lantern” was used again for educational purposes, mainly by the Ministry of Education.

From 1896 to 1897, a stream of newly developed film technology arrived in Japan from the US or France. It was called “Katsudo Shashin” (literally meaning motion picture) in those days, and gradually outgrew its initial status as an exotic spectacle. Original Japanese works began to be made, and as specialized theaters spread it became the center of mass entertainment. Moreover, when four film companies merged into Nikkatsu in 1912, the industry was on the road to consolidation. Matsunosuke Onoe, the first Japanese movie star, gained popularity through his“Kyugeki/Kyuha” (old school) films in Kyoto, and many “Shingeki/Shinpa” (new school) films were made at the studio in Mukojima, Tokyo, where male actors still played female roles in the Kabuki tradition.

The works made in this era used camera tricks during shooting, however this cannot be called a unique cinematic expression, as the action was just filmed with a static camera. So both “Kyuha” and “Shinpa” were not yet in the position of what were later called “period dramas” or “modern dramas”.

Introduction of Motion Pictures to Japan

- Meiji no nihon [Japan in Meiji Era] (1897-99, photo.: Constant Girel, Gabriel Veyre, Tsunekichi Shibata) Approx. 22min.

- Original Cinématographe film fragment donated to Shigeyoshi Suzuki by Louis Lumière (1927)

- Louis Lumière and Shunzo Nakada (1931)

- Poster for Tennenshoku Katsudo Daishashin, Kadoza Theater, Osaka (a. 1903)

- Poster for Vitascope: Katsudo Daishashin (a. 1899)

- Illustration of film screening at Kinkikan Theater, Tokyo (1897)

- Original Equipment of Utsushi-e: Japanese Magic Lantern Show

Momijigari (Maple Viewing)

Momijigari [Maple Viewing] (1899, photo.: Tsunekichi Shibata) Approx. 6 min.

The Advent of Japanese Film Industry

- Pathé Professional camera

- On set, Meguro Studio of Yoshizawa Shoten

- Catalog of magic lantern slides, cinematographs, films and gas generators, etc. (1909)

- Film magazine Katsudo shashin kai (The Cinematograph), no.21 (1911)

- Bioscope camera

- Commemorative photo for Yasunao Taizumi’s departure to Antarctica (1911)

- Nihon nankyoku tanken [The Japanese Expedition to Antarctica] (1912, photo.: Yasunao Taizumi) Approx. 3 min.

- Program sheet of Bancho Engeikan Theater, the exclusive theater of M. Pathé Shokai

- Flyer for Kankoku isshu [Tour of Korea] of Kinkikan Theater, Kanda, Tokyo (1908)

- Kinkikan Theater, Kanda, Tokyo (a. 1907)

- Program sheet for Zigomar of Daiichi Fukuhokan Theater, Kyobashi, Tokyo (1911)

- Program sheet of Daiyon Fukuhokan Theater, Yotsuya, Tokyo (1911)

- Detective story Zigomar (1915)

The Foundation of Nikkatsu

- Poster for Kachusha [Katusha] (1919, dir.: Eizo Tanaka)

- Production still from Asahi sasu mae (1920, dir.: Eizo Tanaka)

- The First issue of the film magazine Mukojima (1923)

- Postcard of Teinosuke Kinugasa as a female impersonator

- Enji Sato and his Top Hat

Tenkatsu and Kokkatsu

- Japanese-made Williamson-type camera

- Handwritten scripts by Amigasa Katsurada

- Genna San’yushi (1915)

- Tendo Jinrikimaru (1917)

- Goro Masamune koshiden (1915, dir.: Jiro Yoshino) Approx. 6min.

- Explanatory script for benshi for Masamune koshiden

- Portrait of Shirogoro Sawamura

- Documents on Kokkatsu

- Invoice for Kokkatsu’s studio and warehouse construction, etc. (1920)

- Budget for salaries for filming unit

- Budget plan for Arupusu no hana and Yama koishi (1920)

- Bill for costumes for Tsumi no otto (1920)

- Kantsubaki [Winter Camellia] (1921, dir.: Ryoha Hatanaka) Approx. 6 min.

Matsunosuke Onoe, the First Movie Star

- Chushingura (1910-12, dir.: Shozo Makino) Approx. 4min.

- Poster for Iwami Jutaro (1917)

- Postcards of Matsunosue Onoe (1914-16)

- Nihon Ginji (1914, dir.: Shozo Makino)

- Raimei rokuro (1915, dir.: Shozo Makino)

- Ishii Genpachiro (1915, dir.: Shozo Makino)

- Komatsu arashi (1915)

- Omaeda Eigoro (1915, dir.: Kichiro Tsuji)

- Kaisoden (1915, dir.: Shozo Makino)

- Kaminarimon taika chizome no matoi (1916)

- Flyer of Fujikan Theater, Tokyo, for Araki Mataemon (1925, dir.: Tomiyasu Ikeda)

Shozo Makino and Makino Production

- Portraits of Shozo Makino

- Handwritten scripts by Rokuhei Susukita

- Edo kaizokuden: Kageboshi (1925, dir.: Buntaro Futagawa, starring Tsumasaburo Bando)

- Aru tonosama no hanashi (1925, dir.: Buntaro Futagawa, starring Ryutaro Nakane)

- Goken Shimizu Ikkaku (1929, dir.: Buntaro Futagawa, starring Juro Tanizaki)

- Memorial album of Jitsuroku chushingura (1928, dir.: Shozo Makino)

- Snapshot from Koiyamabiko (1937, dir.: Masahiro Makino)

- Production stills from Roningai (1928, dir.: Masahiro Makino)

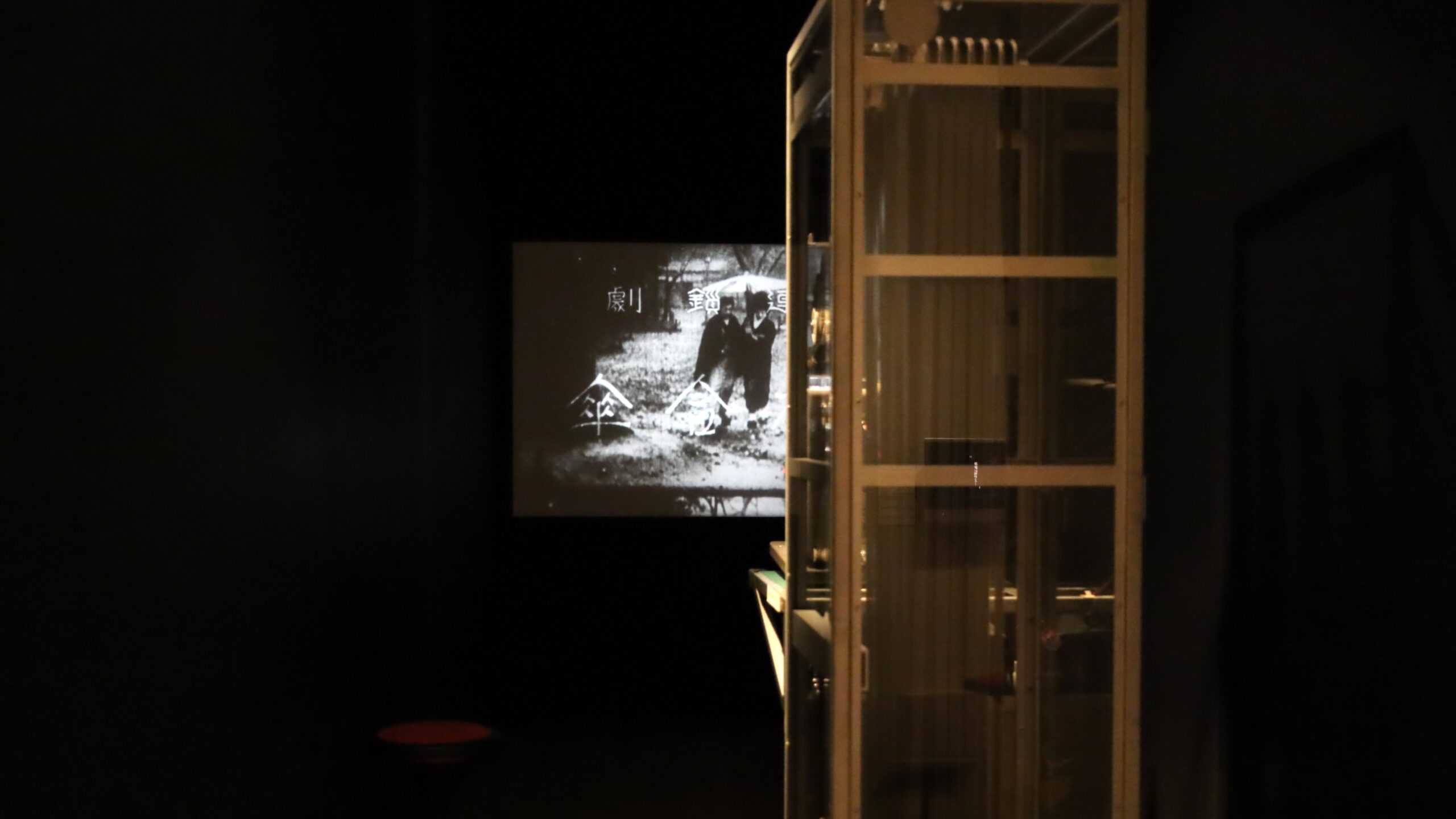

Early Japanese films and benshi performances

Excerpts from Nihon Eigashi [History of Japanese Film](1941)

- Nio no ukisu (1900, photo.: Joji Tsuchiya) starring Ganjiro Nakamura I

- Hototogisu (Production year unknown)

- Aiaigasa (Production year unknown)

- Shoes (1916, dir.: Lois Weber, benshi: Raiyu Ikoma)

- Gen’ei no onna (1920, dir.: Norimasa Kaeriyama)

- Gubijinso (1921, dir.: Henry Kotani)

- Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari (1920, dir.: Robert Wiene, benshi: Musei Tokugawa)

- Sendo kouta (1923, dir.: Yoshinobu Ikeda)

The Golden Age of Silent Film: the 1920s

At the end of the 1910s, “Aikatsuka” (film lovers), who were enthusiastic about western films, started pointing out the immature state of Japanese film, and people such as Norimasa Kaeriyama instigated the “Pure Film Movement” to modernize it. They insisted on the film’s independence by inserting intertitles so that the story could be followed by visual images alone, rather than being dependent on the benshi’s performance. They also abandoned the practice of male actors playing female roles, which enabled the use of actresses and so allowed close-ups of the face.

Such movements influenced works directed by Eizo Tanaka in the old firm of Nikkatsu, and affected the setting up of new companies such as Taisho Katsuei or Shochiku Kinema. As the demand for more up-tempo films increased after the Great Kanto Earthquake (1923), movie stars appeared who were free from conventional theatrical form, and action or comedy films bloomed. In a reflection of cheerful American films, urbanized youth films became popular. But at the same time in period dramas, nihilistic heroes displayed blistering sword fighting, which gained massive popularity. Socially conscious, left-leaning “Keiko Eiga” critical of capitalist society were also made, and they were known for effective crowd scenes. On the other hand, government censorship was also getting tighter.

The Pure Film Movement

- Portrait of Norimasa Kaeriyama

- Production still from Sei no kagayaki (1919, dir.: Norimasa Kaeriyama)

- Script of Chichi yo izuko e (1923, dir.: Norimasa Kaeriyama)

- Portrait of Thomas Kurihara

- Production still from Katsushika sunago (1920, dir.: Thomas Kurihara)

- Snapshot from Hinamatsuri no yoru (1921, dir.: Thomas Kurihara)

- Weekly program from Chiyodakan Theater, Tokyo (1920)

- The first issue of Taikatsu’s film magazine The Movie (1921)

- Narikin (a.1918, dir.: Thomas Kurihara, Harry Williams) Approx. 6 min.

- Production still from Rojo no reikon [Soul on the Road] (1921, dir.: Minoru Murata)

- Program of Rojo no reikon [Soul on the Road] from Kadoza Theater, Osaka, and Kabukiza Theater, Kyoto (1921)

- Portrait of Minoru Murata

- Portrait of Kiyohiko Ushihara

- Portraits of Sumiko Kurishima

- The first issues of Shochiku’s early film magazines Kamata (1922) and Kamata Gaho (1923)

The Katsuben Age

- Poster for the benshi Koyo Komada (a. 1904)

- All-Japan benshi rankings, 8th edition (1917)

- Programs of The Shishiku benshi festival at Denkikan Theater, Asakusa, Tokyo (1920) and Kinema Club, Asakusa, Tokyo (1922)

- Portrait of Musei Tokugawa

- Magazine Warai no okoku (1933-34)

Documentary and Newsreel

- Kanto taishin taika jikkyo [The Cinematic Report on the Great Fire of the Great Kanto Earthquake] (1923, photo.: Shigeru Shirai) Approx. 6 min.

- Flyers for Great Kanto Earthquake documentary at Heiwakan Theater, Ikebukuro, Tokyo and Komagomekan, Hongo, Tokyo (1923)

- Akeley camera

- Snapshot from Kurobe kyokoku tanken [Exploration of Kurobe Valleys] (1927, photo.: Shigeru Shirai)

- Eyemo camera

- Newsreel cameramen of Asahi sekai news (1936)

Le Parvo Camera

- Le Parvo camera (Model L)

- Teinosuke Kinugasa and Le Parvo camera, photographed by Ihei Kimura (1937)

‘A Page of Madness’ and Teinosuke Kinugasa

- Kurutta ippeiji [A Page of Madness] (1926, dir.: Teinosuke Kinugasa) Approx. 5 min.

- Manuscript for Kurutta ippeiji [A Page of Madness]

- Postcard and photos from Kurutta ippeiji [A Page of Madness]

- Poster for Yukinojo henge (1935, dir.: Teinosuke Kinugasa)

‘A Diary of Chuji’s Travels’ and Daisuke Ito

- Chuji tabi nikki [A Diary of Chuji’s Travels] (1927, dir.: Daisuke Ito) Approx. 7 min.

- Snapshot from Zoku ooka seidan (1931, dir.: Daisuke Ito)

- Postcard to Daisuke Ito (1934)

Great Six Jidaigeki Stars

- Denjiro Okochi on the poster for Tange sazen dai ippen (1933, dir.: Daisuke Ito)

- Denjiro Okochi on the program covers of Fujikan Theater Asakusa, Tokyo (1930-31)

- Tsumasaburo Bando on the poster for Mumyo jigoku (1926, dir.: Taizo Riku)

- Tsumasaburo Bando on the poster for Jagan (1926, dir.: Seika Shiba)

- Postcards of Tsumasaburo Bando and his fellow actors

- Postcard for Rakuyo uyu (1931, dir.: Takashi Azuma)

- Kanjuro Arashi on the poster for Kurama tengu (1928, dir.: Teppei Yamaguchi)

- Portrait cards (Bromides) of Kanjuro Arashi

- Notice of Kanjuro Arashi’s joining Makino Production (1927)

- Utaemon Ichikawa on the poster for Jokon (1927, dir.:Shichinosuke Oshimoto)

- Fan magazine Utaemon eiga (1928)

- Chiezo Kataoka on the poster for Tenka taiheiki (1933, dir.: Hiroshi Inagaki)

- Notice of Chiezo Kataoka’s joining Makino Production (1927)

- The first issue of the fan magazine Chiezo eiga (1929)

- Chojiro Hayashi on the poster for Rangun (1927, dir.: Minoru Inuzuka)

- Portrait cards (Bromides) of Chojiro Hayashi / Kazuo Hasegawa

- Chojiro Hayashi (dual role) on the production still from Yukinojo henge [An Actor’s Revenge] (1935, dir.: Teinosuke Kinugasa)

Teikoku Kinema

- Poster for Chuko gidan (1928, dir.: Minoru Ishiyama) and Chuboku Naosuke (1928, dir.: Shintaro Watanabe)

- Poster for Senpu jidai (1930, dir.: Seika Shiba)

Small Gauge Film and Toy Film

- Pathé-Baby 9.5mm camera, formerly owned by Shigeji Ogino

- Pathé-Baby 9.5mm projector, formerly owned by Shigeji Ogino

- An Expression (1935, dir.: Shigeji Ogino) Approx. 3 min.

- Film magazine Nihon Pathé-Ciné (1932)

- Zanjin zanbaken [Man-slashing Horse-piercing Sword] (1929, dir.: Daisuke Ito) Approx. 5 min.

- Lion 35mm hand-operated projector

- Refcy paper film

- Takarabako (1936)

- Norakuro banzai (1937)

Prokino

- Program of Prokino’s third screening event (1930)

- The first issue of the film magazine Prokino (1931)

The Advent of Talkies: the 1930s

Experiments with putting sound on film started in the early days of film history, but in 1927, when The Jazz Singer was released in the US, the film world moved swiftly to the talkie era. Silent films were mainly shot using a hand cranked camera, but when films started to have soundtracks, shooting at a regular speed of 24 frames per second was necessary, and the film industry had to expand to incorporate well-equipped sound recording facilities and the installation of talkie projectors.

Japanese talkies also took off thanks to Shochiku’s success with Madamu to nyobo [Neighbor’s Wife and Mine] (1931), and P.C.L. Studio (later Toho) made a lot of musical films such as Horoyoi jinsei (1933). It can be said that silent films tended to be leaning towards a visually-centered poetic and lyrical expression, but talkies put focus on more realistic expression reflected by the real sound.

At the same time, under its head Shiro Kido’s policy, Shochiku Kamata Studio came to specialize in “petit bourgeois film”, which depicted people’s emotions in everyday life, and directors like Yasujiro Shimazu were quick to master talkie techniques. Even period dramas by directors like Mansaku Itami or Sadao Yamanaka started to depict ordinary characters, which was called “modern drama in costume”, in a move away from the dominant sword fighting. And by using Kansai accents, Kenji Mizoguchi deepened his own realistic expression with films such as Gion no kyodai [Sisters of the Gion] (1936).

Shigeyoshi Suzuki

- Poster for Nani ga kanojo o so sasetaka [What Made Her Do It?] (1930, dir.: Shigeyoshi Suzuki)

- Eastphone disk for Komoriuta [The Lullaby] (1930)

- Poster for Komoriuta [The Lullaby] (1930, dir.: Shigeyoshi Suzuki)

- Production still from Komoriuta (1930)

The Advent of Talkies

- Fujiwara Yoshie no furusato [Home Village] (1930, dir.: Kenji Mizoguchi) Approx. 1 min.

- Poster for Fujiwara Yoshie no furusato [Home Village] (1930)

- Production still from Madamu to nyobo [My Neighbor’s Wife and Mine] (1931, dir.: Heinosuke Gosho)

- Flyer for Madamu to nyobo [My Neighbor’s Wife and Mine]

- Script for Tonari no zatsuon (1931)

Shochiku Modernism

- Portrait of Heinosuke Gosho

- Notification of promotion to Heinosuke Gosho

- Marionette for Meiji haruaki (1968, dir.: Heinosuke Gosho)

- Poster for Tonari no Yae-chan [My Little Neighbor, Yae] (1934, dir.: Yasujiro Shimazu)

- Poster for Kaze no naka no kodomo [Children in the Wind] (1937, dir.: Hiroshi Shimizu)

Kinuyo Tanaka

- Portrait cards (Bromides) of Kinuyo Tanaka

- Poster for Jinsei no onimotsu (1935, dir.: Heinosuke Gosho)

- Kinuyo Tanaka’s personal items

Yasujiro Ozu

- Portraits and snapshots of Yasujiro Ozu

- Poster for Shukujo wa nani o wasuretaka [What Did the Lady Forget?] (1937, dir.: Yasujiro Ozu)

- Poster for Tokyo monogatari [Tokyo Story] (1953, dir.: Yasujiro Ozu)

- Script for Tokyo monogatari [Tokyo Story]

Nikkatsu Tamagawa Studio

- Poster for Kagirinaki zenshin (1937, dir.: Tomu Uchida)

- Photos from Tsuchi [Earth] (1939, dir.: Tomu Uchida)

- Snapshot from Tsuchi: Tomu Uchida (far left), cinematographer Michio Midorikawa (at top)

- Rush film of Tsuchi [Earth] (1939) Approx. 5 min.

- Pen tray made by Tomu Uchida

- Portrait of Isamu Kosugi

- Jointly signed flag to commemorate the location shooting of Tsuchi to heitai [Mud and Soldiers] (1939, dir.: Tomotaka Tasaka)

- Photos from Tsuchi to heitai (1939)

- Program for Tsuchi to heitai at Ginza Gekijo, Tokyo

Directors Guild of Japan

- Prospectus of Directors Guild of Japan (1936)

- Letter to Teinosuke Kinugasa (1936)

- Photo at the foundation meeting of Directors Guild of Japan (1936)

From P.C.L. to Toho

- Official notice of the foundation of Toho (1937)

- Poster for Wakai hito [Young People] (1937, dir.: Shiro Toyoda)

- Poster for Donguri Tonbee (1936, dir.: Kajiro Yamamoto)

- Poster for Tokkan ekicho (1945, dir.: Torajiro Saito)

- Photo album of Hawai mare oki kaisen [The War at Sea from Hawaii to Malaya] (1942, dir.: Kajiro Yamamoto)

Sadao Yamanaka

- Portrait of Sadao Yamanaka

- Rubbing from the memorial stone of Sadao Yamanaka

- Production stills from Ninjo kamifusen [Humanity and Paper Balloons] (1937, dir.: Sadao Yamanaka)

Kawai Eiga / Daito Eiga

- Poster for Hirai Gonpachi (1928, dir.: Koji Oka)

- Poster for Hi no kuruma Oman (1928, dir.: Junzo Sone)

- Film magazine Daito Eiga (1936)

- Still photo albums of Daito Eiga

Japanese Film in Wartime: from the Late 1930s to 1945

Film, discovered at the end of the 19th century, developed in parallel with modern warfare in the 20th, the so-called “century of warfare”. Japanese film also came up with its first breakthrough, when a record of the Russo-Japanese War was made by an embedded crew, and via the Manchurian Incident to the Sino-Japanese War of the late 1930s, its importance increased as a propaganda medium, in support of the war.

The patriotic “national film policy” movement was instituted under the new “Film Law” in 1939 with the aim of contradicting the negative image of Japan introduced in foreign-made films. The law clearly required registration of film staff, advance script censorship, and enforced screenings of culture films and newsreels, as well as restriction of foreign films. And under these conditions, as film was seen as a military resource, Nikkatsu, Shinko Kinema, and Daito Eiga were merged to be a new company, Daiei. Also, films were sent to countries already under Japanese colonial occupation such as Taiwan, Korea, and Mainland China, as well as to South East Asia as an advance party to win hearts and minds as the Pacific War advanced.

Manufacture of Movie Projectors in Japan

- Projection head: Royal Model H, manufactured by Komitz

- Sound head manufactured by Rola

- Lamphouse manufactured by Matsuda

- Stand manufactured by Komitz

Government Control on Film and Film Law

- Film censor stamps used by the Ministry of Home Affairs

- Motion Picture Film Censor Report (1926) and Censor Card

- Censored script for Naniwa erejii [Osaka Elegy] (1936, dir.: Kenji Mizoguchi)

- Illustrated Film Law (1939)

- Poster for Nippon nyusu 78 go [Nippon News No.78](1941)

- Poster for Shori no hi made [Until Victory Day] (1941, dir.: Mikio Naruse)

- Directory of Japanese movie actors (1943)

Colonial Policy and the Cinema

- Askania camera

- Nyan’nyan meyaohoi (1940, edit.: Kozo Akutagawa) on location

- Poster for Shanghai (1938, edit.: Fumio Kamei)

- Film magazine Manshu Eiga [Japanese, Chinese](1937)

- Company bulletin Kaei Tsushin (1943)

- Portrait photo of Li Xianglan (Yoshiko Yamaguchi)

- Production photo from Mi yue kuai che [Honeymoon Express] (1938, dir.: Shinji Ueno)

- Poster for Wan shi liu fang (1942, dir.: Wancang Bu)

- Private photo album of Nankai no hanataba [Bouquet in the Southern Seas] (1942, dir.: Yutaka Abe), formerly owned by Tadashi Iimura

The Postwar Golden Age: from 1945 to the 1950s

After defeat and then through the occupation period, Japan aimed to rebuild its broken society in the 1950s. The film industry developed alongside this new spirit, as if encouraging people’s efforts, and film enjoyed its position as the “king of entertainment”.

It was an artistically glorious era when works by Akira Kurosawa or Kenji Mizoguchi gained worldwide acclaim, symbolized by Rashomon’s Golden Lion Award from the Venice International Film Festival. At the same time, the film industry was in its first ever boom period. Annual cinema admissions reached an all time high of 1,127,450,000 in Japan in 1958, and in 1960 annual production exceeded 547 titles in feature films alone, with the number of movie theaters hitting 7,457. This was down to six major companies; Shochiku, Toho, Daiei, Toei, Nikkatsu, and Shintoho (five after the bankruptcy of Shintoho in 1961), who each controlled the entire process of film circulation from production to distribution and box office, so that their films reached theaters all over the country.

Japanese film in those days was also characterized by the advance of new technology, such as the arrival of color film, starting from the first Japanese color feature film Karumen kokyo ni kaeru [Carmen Comes Home] (1951), and advanced special effects techniques in films such as Gojira [Godzilla] (1954).

Mitchell NC Camera

Mitchell NC Camera

Natco Projector

Natco 16mm projector

Akira Kurosawa

- Manuscript for Rashomon (1950, dir.: Akira Kurosawa), formerly owned by Sojiro Motoki

- Golden Lion Trophy for Rashomon from the Venice International Film Festival, formerly owned by Sojiro Motoki (1951)

- Poster for Rashomon

- Provisional list of film titles for Ikimono no kiroku [I Live in Fear] (1955, dir.: Akira Kurosawa), formerly owned by Sojiro Motoki

- Costume designs for Dodes’kaden (1970, dir.: Akira Kurosawa) by Shinobu Muraki

- Private photo album of Ikiru (1952, dir.: Akira Kurosawa), formerly owned by Takashi Shimura

Kenji Mizoguchi and Hiroshi Mizutani

- Poster for Saikaku ichidai onna [The Life of Oharu] (1952, dir.: Kenji Mizoguchi)

- Set designs for Shin heike monogatari [Taira Clan Saga] (1955, dir.: Kenji Mizoguchi) by Hiroshi Mizutani

- Costume designs for Shin heike monogatari [Taira Clan Saga] by Hiroshi Mizutani

- Death mask of Kenji Mizoguchi

- Hiroshi Mizutani donating Kenji Mizoguchi’s death mask to the Cinémathèque française

- Death mask of Hiroshi Mizutani

- Photo album of Chikamatsu monogatari [The Crucified Lovers] (1954, dir.: Kenji Mizoguchi)

Mikio Naruse

- Set designs by Satoru Chuko for Yama no oto [The Sound of the Mountain] (1954, dir.: Mikio Naruse)

- Photo album of Okaasan [Mother] (1952, dir.: Mikio Naruse)

The First Japanese Color Feature Film and Keisuke Kinoshita

- Poster for Karumen kokyo ni kaeru [Carmen Comes Home] (1951, dir.: Keisuke kinoshita)

- Bookmark with color film frame for Karumen kokyo ni kaeru [Carmen Comes Home]

Konicolor System

- Konicolor Monoplane One-shot Camera No.101 (1953)

- Production still from Midori haruka ni (1955, dir.: Umetsugu Inoue)

Special Effects in Japanese Film

- Poster for Gojira [Godzilla] (1954, dir.: Ishiro Honda)

- The Record of Screen Process Tests, published by Daiei Tokyo Studio(1953)

Independent Film Production Movement

- Poster for Nigorie [An Inlet of Muddy Water] (1953, dir.: Tadashi Imai)

- Photo album of Himeyuri no to (1953, dir.: Tadashi Imai)

- Script of Shinku chitai [Zone of Emptiness] (1951, dir.: Kozaburo Yoshimura)

- Script of Itsuwareru seiso (1951, dir.: Kozaburo Yoshimura)

- Poster for Hadaka no shima [The Island] (1960, dir.: Kaneto Shindo)

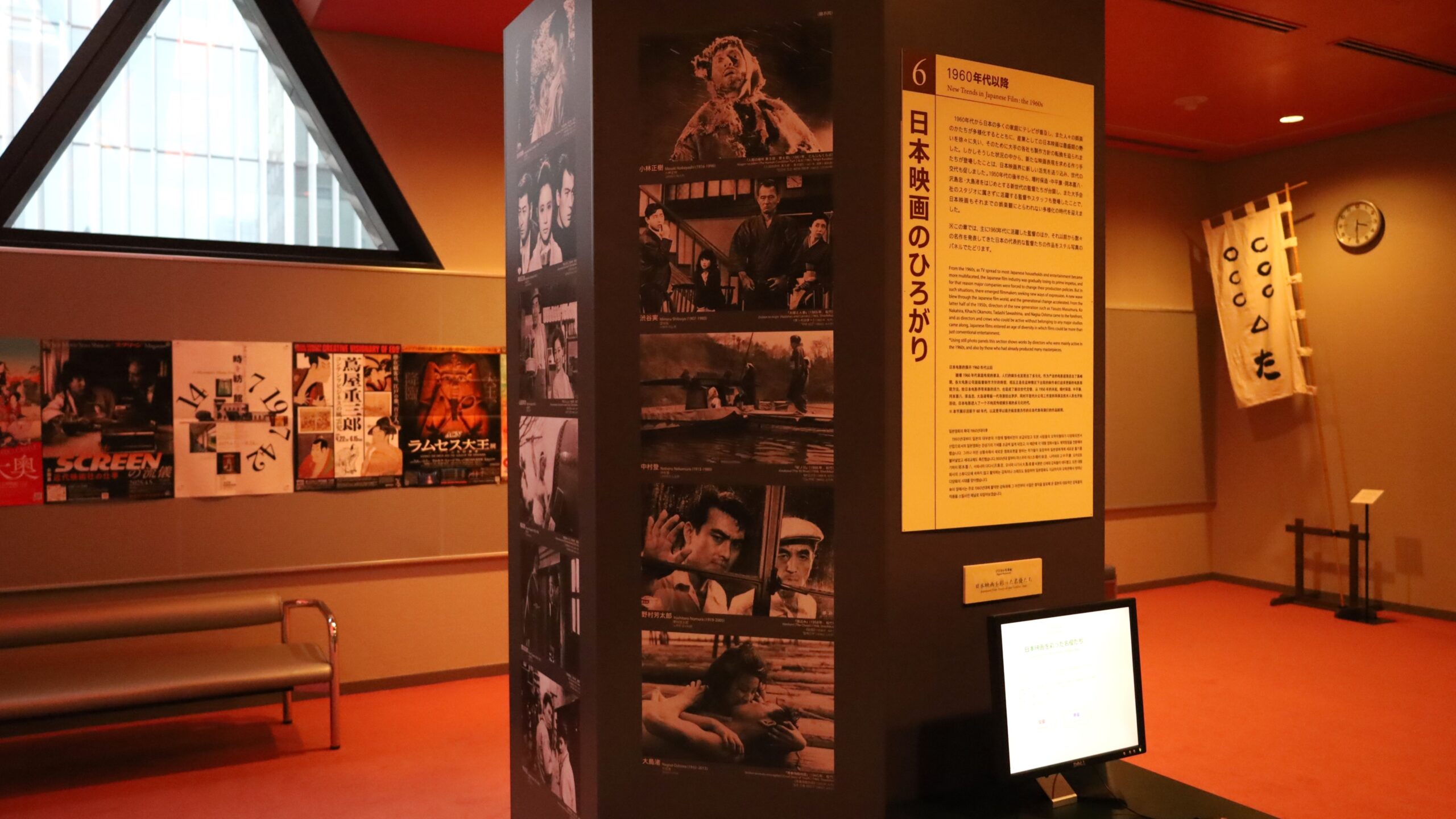

New trends in Japanese Film: the 1960s [Reception area]

From the 1960s, as TV spread to most Japanese households and entertainment became more multifaceted, the Japanese film industry was gradually losing its prime impetus, and for that reason major companies were forced to change their production policies. But in such situations, there emerged filmmakers seeking new ways of expression. A new wave blew through the Japanese film world, and the generational change accelerated. From the latter half of the 1950s, directors of the new generation such as Yasuzo Masumura, Ko Nakahira, Kihachi Okamoto, Tadashi Sawashima, and Nagisa Oshima came to the forefront, and as directors and crews who could be active without belonging to any major studios came along, Japanese films entered an age of diversity in which films could be more than just conventional entertainment.

*Using still photo panels this section shows works by directors who were mainly active in the 1960s, and also by those who had already produced many masterpieces.

Japanese Animation

Japanese animations are now shown all over the world and highly esteemed, but this was not achieved overnight. It is said that the history of Japanese animation goes back to 1917. It had its origins in “Manga Eiga” tried by three pioneers, and other animators worked on cutout animations, shadow animations, or cel techniques, but even after World War II independent or small-scale group productions continued.

The biggest turning point was when Toei, a major feature film company, founded Toei Doga (now Toei Animation Co., Ltd.) in 1956. This opened up the possibility of feature length animation films for theatrical release, and the animation industry flourished. As a result many qualified animators appeared, and Japan went on to become an “animation nation” with countless theatrical releases and TV programs. On the other hand, for independently made artistic animation, Noburo Ofuji was a lone figure in the 1950s, but later on various animators appeared, such as Tadanari Okamoto and Kihachiro Kawamoto, who specialized in puppet animations. Even now a lot of them are active inside and outside of Japan.

The Origin of Japanese Animation

Namakura gatana (or Hanawahekonai meito no maki) (1917, dir.: Jun’ichi Kouchi)

Noburo Ofuji

- Portrait of Noburo Ofuji

- Shikisai manga no dekiru made [How to Make a Color Animation Film] (1937, dir.: Shigeji Ogino) Approx. 5 min.

- Poster for Tengu taiji (1934, dir.: Noburo Ofuji)

- Paper artwork by Noburo Ofuji

- Shadowgraph original drawing by Noburo Ofuji for Yuureisen [The Phantom Ship] (1956)

- Cel animation shooting equipment of Noburo Ofuji

Toei Animation

- Poster for Hakujaden [The Tale of the White Serpent] (1958, dir.: Taiji Yabushita)

- Storyboards for Koneko no Sutajio [Kitten’s Movie Studio] (1959, dir.: Yasuji Mori)

- Storyboards for Hakujaden (1958)

- Character dolls for Anderusen monogatari [Fables from Hans Christian Andersen] (1968, dir.: Kimio Yabuki)

- Character dolls for Chibikko Remi to meiken Kapi (1970, dir.: Yugo Serikawa)

- Cels from Anderusen monogatari

Tadanari Okamoto

- Porarait of Tadanari Okamoto

- Homu mai homu [Home My Home] (1970, dir.: Tadanari Okamoto) Approx. 4 min.

- Papercrafts for Homu mai homu [Home My Home] (1970, dir.: Tadanari Okamoto)