2018|Rising Filmmakers Project|Conversations with filmmakers and guests

You can read talk events after screenings by filmmakers and guests in this page.

There are also talks before screenings by film festival representatives and filmmakers’ interviews available.

(Information on the event, films and filmmakers is here)

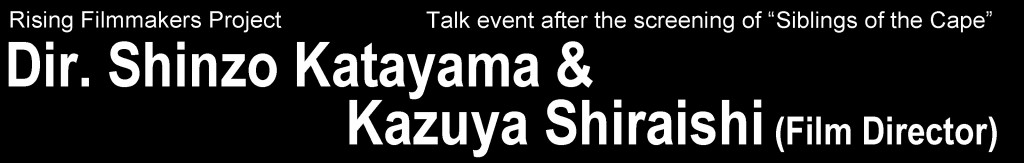

“Siblings of the Cape” Jan.26(sat)11:00-

Dir. Shinzo Katayama & Kazuya Shiraishi (Film Director)

“Dead Cop”, “ICHIMONJI KEN Prologue Kung Fu Boy VS Murder Karate Man” Jan.26(sat)14:05-

Dir. Yu Nakamoto & Yuji Shimomura (Action Director)

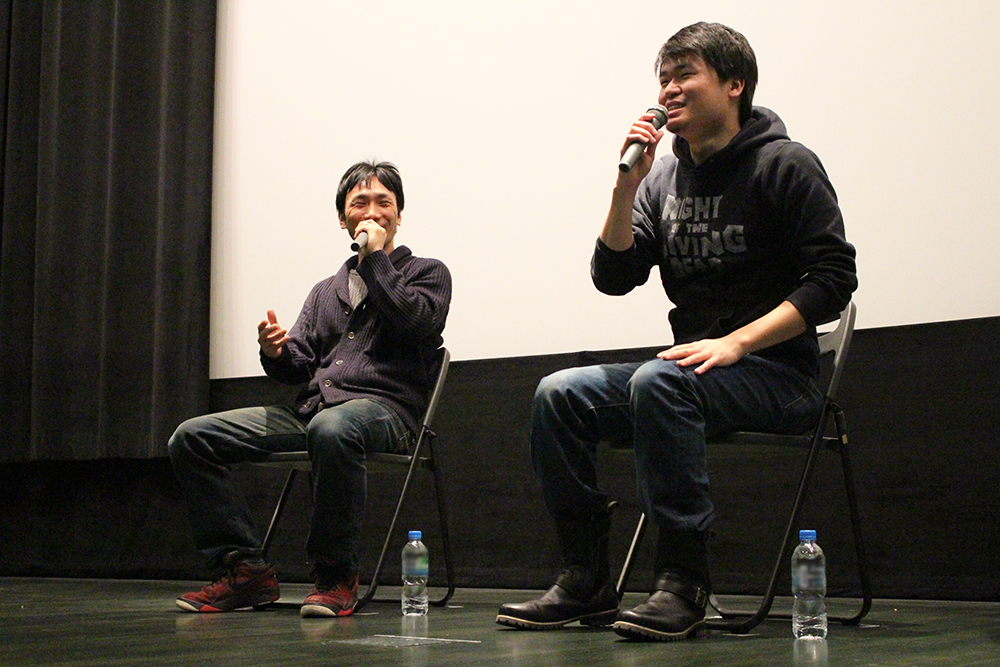

“ED OR (THE UNEXPECTED ERECTION OF YOU)” Jan.26(sat)17:15-

Dir. Hikaru Nishiguchi & Kosuke Mukai (Scriptwriter)

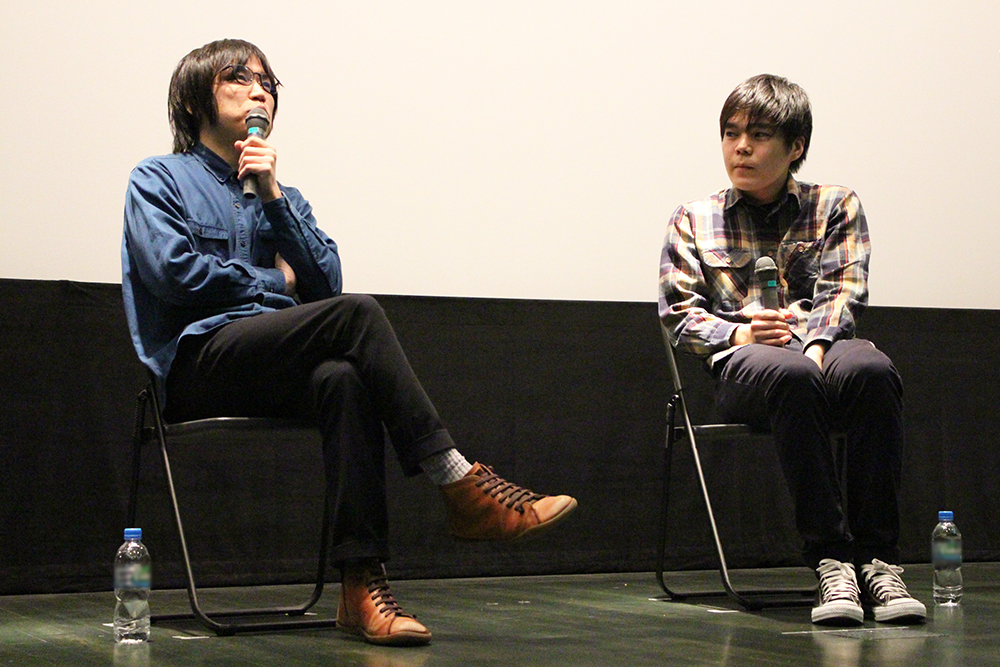

”Orphans' Blues” Jan.27(sun)11:00-

Dir.Riho Kudo & Koji Fukada (Film Director)

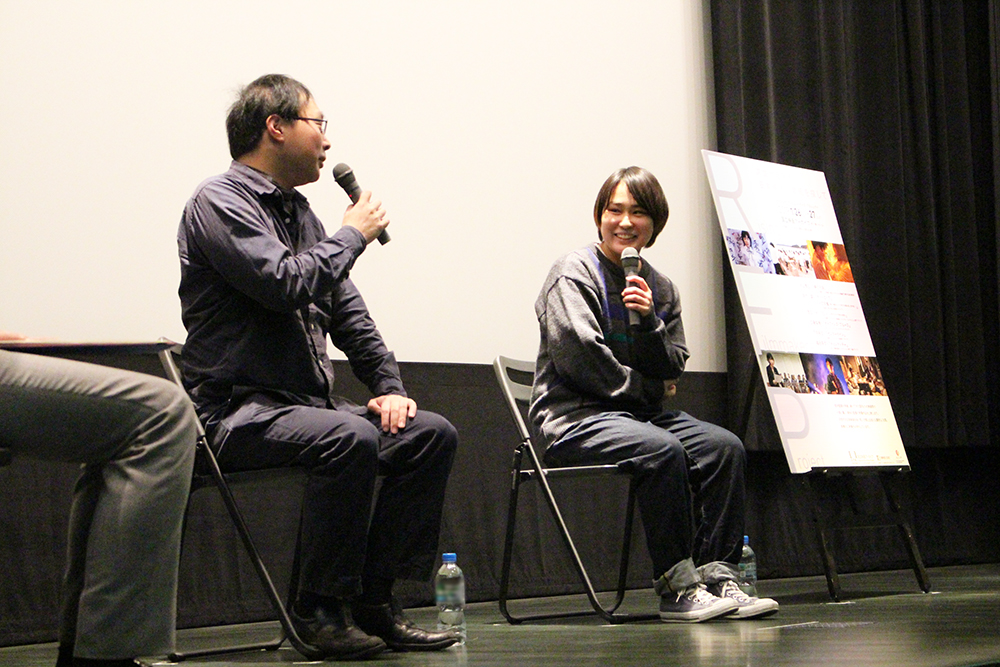

“CenterLine” Jan.27(sun)14:05-

Dir. Takumi Shimomukai & Takashi Yamazaki (Film Director)

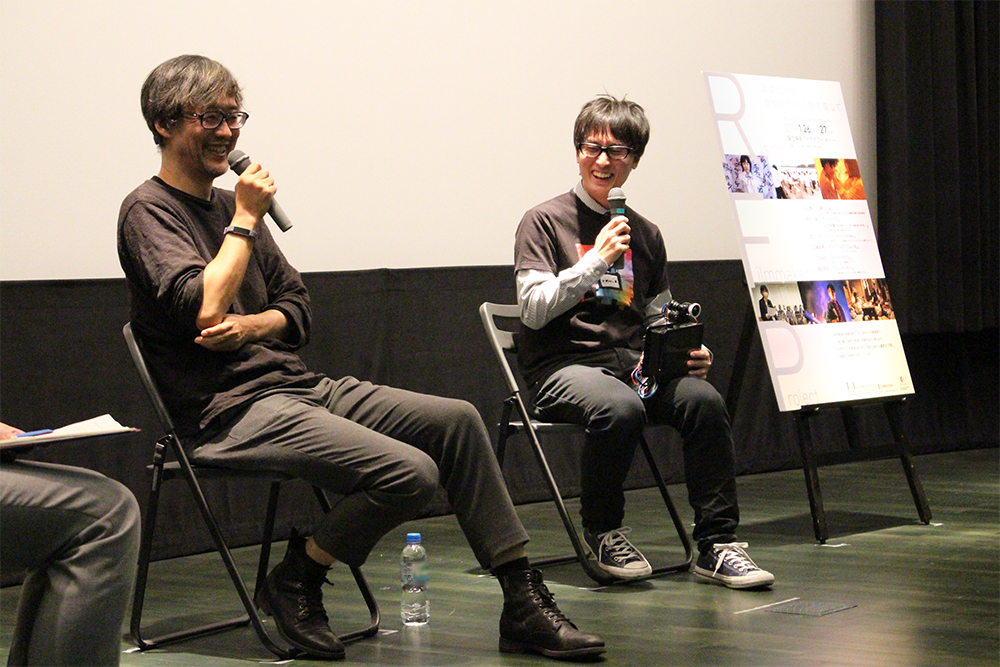

“Chonticha at end of the summer” Jan.27(sun)16:50-

Dir. Mei Fukuda & Isao Yukisada (Film Director)

January 26, 2019 at B1 Theatre, National Film Archive of Japan

For information of the film and the director, please visit here.

―Can you tell us why you aspired to be a film director and how you got to know Mr. Shiraishi?

Katayama: I’m Shinzo Katayama, the director of this film. Thank you all for coming today. I had wanted to be a film director since I was in junior high, and at the age of 20 or so, went to study for a year at Eizo-juku, a film institution in Takadanobaba at the time. I had been making films independently on my own but was getting discouraged that I had no talent. I managed to find work as assistant director on professional productions. After a few years, vanity got the best of me and I wanted to direct. So I saved up and decided to spend a year making this film.

I knew that Mr. Shiraishi had also graduated from Eizo-juku and that he was already doing great work in the industry. I had the chance to work with him as third assistant director when he was first assistant director on a 40-minute film titled “Yasushi Inoue ‘The Hunting Gun’” – it was one of the NHK drama series “Rodoku Kiko Nipponno Meisaku (Travelogue Reading of Japanese Classics)” directed by Isao Yukisada.

―Mr. Shiraishi, tell us about your impressions and what you noticed on watching “Siblings of the Cape”.

Shiraishi: I had asked for a DVD to watch beforehand, but I wanted to see it again on the big screen today. And the impression I got was different from watching the DVD on my television at home. At the briefing early today, I was told that I should “Walk up to the stage from your seat.” But the film was so good, something “overwhelmed me” and I had to step out the lobby before I could go up. There is a strong hand in the directing –the lighting was choreographed and the sound was designed almost flawlessly. I was in bliss watching Yuya Matsuura throughout the film. And you thoroughly captured the physicality of Misa Wada, who played the incredibly rewarding acting role of the person with mental disabilities.

Something I noticed is how the storyline doesn’t diverge from what is familiar to people – it follows more or less the expectation of “I can see how this will go.” Though that (predictability) in itself is not a negative thing. I would think on the contrary that this testifies to its strength, because it would never have worked if the film wasn’t strong enough. Meanwhile, there is no reference to how society and the welfare system fails the protagonists, in the vein of “I, Daniel Blake” (2016 / dir: Ken Loach). There’s only the world of the factory man played by Kenji Iwaya. Oh, and there’s the policeman who’s a friend. But he’s not really failing the characters, so basically (the society that’s being depicted in this film) is the factory alone. Did you ever think about including the issue of state support during the script writing stage? That’s about the only question I had.

―Did you ever consider including the issue of welfare?

Katayama: At first I did. For example, I thought of a scene where welfare workers come to the house. But then the story would be diverted. I did know that in real life there are occasionally such cases, but I wanted, instead of using social satire or being indignant about the welfare system today, to aim towards a more universal, perhaps a somewhat fable-like approach. I wanted to avoid a fixed historical time frame.

Shiraishi: I saw how you avoided depicting the government system and understood it to be recognized as a given, that “here’s the Japanese system.” I noticed it, but it’s not a mistake, because it’s a fair option. I just wanted to ask you if it was intentional.

―Anything else?

Shiraishi: About his technical choices in directing. One of the sources of Mr. Katayama’s strengths lies in the positioning of the actors at the start of a scene. Ms. Wada’s action leaves a strong impression since you use the depth and width of the space to move her around. Seeing how you can set up the first position and direct the movement so brilliantly, I am sure you will manage to work in any genre of filmmaking. Was all that movement an intentional choice? Like, did you give precise instructions? “Ms. Wada goes there while this other person is speaking over here” and such?

Katayama: I did give some instructions. For example, I did for the housing estate scene (when there’s the two characters and there’s a pregnant woman in the back, and Ms. Wada is in the foreground at first but notices the woman and moves to the back).

Shiraishi: I think the beauty of this film originates in the positioning of the actors, or characters. It’s not just a chance setup on location, but Mr. Katayama’s instinctive ability to measure how the sun shines in the moment of the shot, where the window is located as you enter the room, how to get the light behind you, and to note which movement would give you darkness. I was truly impressed by how it all seemed to be done so effortlessly.

The other thing for this kind of independent film is, “how to intentionally include troublesome scenes and shots.” Some filmmakers brag that these types of shots are cool or whatever and go out of their way to make them happen. But in this film, those shots feel organic. The first example is the one everyone remembers, the poop battle scene. That was incredible. I was wondering how you would shoot that. How did you come up with that?

Katayama: I was just wondering how a crippled person would get away from that kind of situation and the idea came to me. “It’s gotta be poop,” I thought.

Shiraishi: And the fact that the perpetrators are junior high school kids is just brilliant. You are showing that the protagonists are at an even lower status than these kids, and the act of throwing poop at them works. Also, the interchanging of men in the sexual act – that’s also a difficult shot that you wouldn’t attempt if you didn’t have an idea how to make it work.

Katayama: The actors changed when they were out of the camera frame. I had to plan very carefully and spent around eight hours filming it.

Shiraishi: You would only think of that kind of shot if you had experience as assistant director. Without prior experience, you wouldn’t know how far you could go, or “if you do that, we can do this.” And it’s something the director has to think up because the crew would never come up with that kind of idea. I’m amazed that you took up the challenge. Eight hours! Only in independent film can you use time so luxuriously. On a commercial film, they’d say, “Okay, you have 30 minutes.” Only if you manage, it’s one way you can grasp your chance – it’s how you can leave your mark despite the limited resources and poverty of the Japanese commercial film world.

―Did you ever feel that your experiences as assistant director were beneficial?

Katayama: Yes I did, on specific sets, and also overall I could recognize what it was I could or could not do. Working with an extremely small crew, I could judge for example “if we had this person and this person, we could manage with just a few people.” If I hadn’t been assistant director, managing the budget wouldn’t have been a given. Thanks to that career, I could fathom the balance of things.

Shiraishi: This kind of film should be seen by lots of people. It belongs in the category of Shohei Imamura, ATG (Art Theater Guild), Nikkatsu Roman Porno, and other great Japanese masters who were adamant to “make the film we want to make, even without funds.” I was overjoyed to discover such a film that is not easily made. I especially feel pleased because there is no future for Japanese cinema if the actors don’t come to gain from this kind of film. The press praises actresses today for “courageous physical acting” when they just cut long hair short. I am curious how the media will write about this film.

I think Mr. Katayama will be offered film projects once this film gets publicly released. Japanese film producers tend to propose films to directors who take risks like him. I have the feeling he will successfully find his place within the mainstream or commercial film industry.

―Do you plan to continue directing films?

Katayama: Yes, I do. As much as I can, I hope to make films originating from within myself.

Moderator: Naoki Motomura

Translator: Asako Fujioka

January 26, 2019 at B1 Theatre, National Film Archive of Japan

For information of the film and the director, please visit here.

―As a way of introducing yourself, tell us how you came to make this film.

Nakamoto: Hello everyone, my name is Nakamoto. I appreciate that so many people turned out today. I had always loved films since childhood, but at first I got a job as a company employee and then did web design for around four years. But since I never stopped loving movies and had this desire to direct a film, I (quit my job) and entered a 3-year vocational school in Tokyo. I said to myself, “If it doesn’t work out in three years, I’ll give up.” I filmed “Dead Cop” in my first year at school, and “ICHIMONJI KEN” in my second year.

―This Rising Filmmakers Project invites a film professional of your choice to come meet you and give advice. Mr. Nakamoto, how long have you been admiring Mr. Shimomura’s work in action direction?

Nakamoto: Yes, I’ve been following him on Twitter all along, and knew him as an important action director. As a fan, I just thought “I’d love to meet him.”

―Mr. Shimomura, you are a director as well as action director. Can you explain the work of an action director?

Shimomura: Hello. My name is Yuji Shimomura. The work of an action director, in a few words, is directing action scenes in films and dramas. That involves character establishment and scene situations, so naturally you have to structure the drama in addition to the action. In our case, we ask the stuntmen to act out the movements and we film the entire scene with cuts, angles, and camera work intact to compile a video board (“video conte” in Japanese). It’s what you call Pre-Vis (pre-visualization). Since I also used to make indie films, it’s like filming in that spirit. We prepare the video board, discuss it with the other staff, get the actors to train their movements accordingly. Then the action director goes on to supervise the real take and participate in the editing.

So, what genre of films do you like, Mr. Nakamoto? I see in your work that you seem to set your historical timeframe a bit in the past, using the walkmans, TVs with attached video consoles, or clothing and music from the past. It feels like an homage to movies of the 70s and 80s, so I wonder if you have an attachment to that generation of films.

Nakamoto: I was born in 1991 and grew up watching movies on the television slot “Friday road SHOW”. I’m of the generation when movies from the 80s and 90s were regularly being shown on TV. I didn’t have the money to go to the cinema, so I was always watching the TV runs on my videotape recorder.

In terms of genre, I like foreign films. Like “The Terminator” (1984, dir: James Cameron). Among Kungfu films it was “Drunken Master II” (1992, dir: Lau Kar-Leung). I also loved Bruce Lee. My devotion to those kinds of films pushed me to make films like them. I love special effects, too, and I made a parody of “Karate-Robo Zaborgar” (2010, dir: Noboru Iguchi) myself. I made films inclusive of the jumble of things I loved. I tried to reproduce… or maybe aspire to a generation of films that I loved.

Shimomura: I also started out doing action films, but before that it was “Star Wars” (1977, dir: George Lucas). It’s just like you said, Mr. Nakamoto, they used to broadcast movies on TV every day. I’m of the generation that grew up watching films on television, too, so I feel your films are, like, my taste.

Nakamoto: Thank you, I’m so pleased.

―Mr. Shimomura, as action director, what do you think of the action sequences in his film?

Shimomura: They are of high quality. From a pro’s perspective, obviously there are things that could be better. But I think that if he continues to press on doing what he really likes, the quality of the work will become more and more refined.

―Any advice for the future on action directing?

Shimomura: This might be a minute point, but… if you spend a bit more detail in planning the cutting or directing of the rising emotions in the drama within the action, this would connect to the second half of the film and further heighten the intensity. The movements are well executed but I feel maybe there’re not enough shots to present the emotions.

Nakamoto: I understand. Thank you.

Shimomura: Overall, it’s fantastic work. You really set fire to that leg, didn’t you?

―What kind of safety measures would a professional production take if you needed to set fire to someone’s leg?

Shimomura: We would use fire gel or heat resistant clothing for safety. I was wondering how you did it for this film.

Nakamoto: The actor wore layers of pants. It’s just additional padding underneath.

Shimomura: And you extinguished the fire when it got too hot?

Nakamoto: Yes, we cut right away. We’d put out the fire, then light it again and “Rolling, action!” It took a crushing long time to do that sequence.

Shimomura: Wonderful. One shot, then extinguish, one shot, then extinguish – right?

Nakamoto: That’s right. If the shot didn’t work, we’d do it again. His jeans were burning away, so we had to prepare new ones. That’s how it was.

―What were the problems or difficulties you faced during the filmmaking, Mr. Nakamoto?

Nakamoto: It’s building up the space. That’s something I had always felt difficult in action sequences, and I don’t think I got it right for this film. I can’t think of how to shoot action while utilizing a location in a three-dimensional way. I had always rehearsed in empty classrooms at school, so my ideas are always about moving around in an open space. It’s a technical thing, but it is also a lack of creative ideas.

Shimomura: I saw some prop-like things near the riverbank, like a drum barrel. You could use that, or the motorcycle. Was that yours?

Nakamoto: Yes, it’s mine.

Shimomura: The character could ride the motorcycle around to create movement within that limited space, or have the character dodge around the motorcycle. You could also set fire to it.

Nakamoto: Then I’ll have to junk it!

Shimomura: Well, if it’s yours it shouldn’t be a problem (laughter). Once you go that far, the odds get higher. The other thing was, most of the action was face-to-face. You could add zig-zag movements like, someone escaping around to the back but then the other keeps chasing. That way, the surrounding objects and environment will be drawn into the action sequence.

―Did you end up filming on the riverbank because indie filmmakers find it hard to find places to film freely?

Nakamoto: Yes, we can only film in places where there are not too many people and where they won’t yell at you.

Shimomura: Over 20 years ago, I was into making lots of indie movies, too. They were all action flicks, and all filmed in the neighborhood park. I thought hard about what kind of action sequences I could choreograph, using all the playground equipment there were. We just ignored the kids who were playing there (laughter). There really was no other place to film, and we only had the park.

Nakamoto: I’m also at a loss for gun action situations. I like Jackie Chan so I use a lot of bare-handed fighting. How do you come up with movements using weapons like guns or knives?

Shimomura: Before I became an action director, I worked as a stunt man for a long time. Action movies demand different skills, so learned all kinds of wushu, martial arts and weapon handling. As an action director now, I am still studying but I get to work together with specialists of each field.

Nakamoto: I’m curious, how did you become an action director, Mr. Shimomura?

Shimomura: You could be one too, if you keep at it. From the impression of your films, I am sure you will become someone in high demand. At that point, depending on who you meet along the way, you will be able to forge the road you want to travel.

Nakamoto: Thank you. I’m still a student and so whenever I meet someone who is working successfully in the film industry, I always wonder how they got to be where they are (as professionals).

Shimomura: To tell the truth, I would advise you to keep making independent films and not go pro just yet. I want to see some more of your indie work. You should follow what you love just a bit more, to a certain depth. Once you enter the business, sometimes you get to do what you wanted to do, but more often you find you can’t. I think you should just do the stuff that excites you until we get to see your signature, your unique voice as a filmmaker. So don’t go pro yet, and just keep making films.

―Is your ambition to be a director or an action director, Mr. Nakamoto?

Nakamoto: Director. I love thinking up stories and I want to keep on directing. Actually, I’ve received an offer to do a commercial film – though it’s not like real professional. It’s very low budget so I’m not sure whether it will work out, but I do want to try it out. I have no idea what the future will bring and I’m full of anxiety, but being able to meet Mr. Shimomura today gave me courage.

Shimomura: Does the project have action in it? If so, let me know. I’ll be happy to offer a hand.

Nakamoto: Seriously? Thank you!

Moderator: Naoki Motomura

Translator: Asako Fujioka

January 26, 2019 at B1 Theatre, National Film Archive of Japan

For information of the film and the director, please visit here.

―Tell us about your background and how you came to film “ED OR (THE UNEXPECTED ERECTION OF YOU)”.

Nishiguchi: I’m a graduate of Osaka University of Arts and was hoping to direct my own graduation thesis film. I started out studying cinematography and really enjoyed working on film stock, but then I felt the ambition to direct. So the graduation film is my directorial debut.

―Kosuke Mukai, you are also from the same university. What’s your impression of this film?

Mukai: I enjoyed it. It’s not trying to be profound. I watched it wondering whether it is “typical of an Osaka University of Arts student film” but I guess there’s no such thing as typical. It’s probably Mr. Nishiguchi’s own uniqueness. The way you set up the classroom on the beach took me by surprise – “Oh, a classroom by the sea!” It reminded me of the early films of Yoshimitsu Morita. When I first saw the flyer to today's event, I thought “maybe it’s a difficult film,” but I was relieved to find that my hunch was wrong (laughter). I was glad to see it was the kind of film I like.

―Mr. Nishiguchi, what was the idea behind setting up the classroom on the beach?

Nishiguchi: I had this image of Sumire, the heroine, as a “woman of the sea”. And so I thought the first meeting with the protagonist would be a school classroom, but by the sea. And I just went off to shoot it like that.

Mukai: That scene is set up as a space distinctively separated from reality. Similarly, Sumire’s house is so bare, with no furniture, but you make it work. “Right on target. He’s good!” – I thought. You are taking advantage of the fact you are working with no budget.

―What did you find troubling or problematic in shooting this film?

Nishiguchi: Everything, all the time. It was my first time to direct, and there was lots in the script that I changed in my mind but forgot to tell the crew. I took it for granted that they would get it, but when I told them “Here’s how we’ll shoot it,” they often said, “You never told us!” And I felt bad for them.

―Mr. Mukai’s graduation film from Osaka University of Arts was “Hazy Life” (1999, dir: Nobuhiro Yamashita, script: Kosuke Mukai, Nobuhiro Yamashita), which won the Fantastic Off Theater Competition of Yubari International Fantastic Film Festival in 2000. You’ve been working with Mr. Yamashita ever since. How do you go about writing scripts?

Mukai: At first we would pitch ideas to each other and write together. We would start with a memo either one of us had written and for example Yamashita would play character A and I would be character B and start talking to each other. Once we get things rolling, we would write it down.

During your time at Osaka University of Arts, Mr. Mukai, there was cinematographer Ryuto Kondo (known for “Shoplifters” (2018, dir: Hirokazu Kore-eda)) and actor Hiroshi Yamamoto (lead actor in “Artist of Fasting” (2016, dir: Masao Adachi) among your classmates. It was a golden age of talent.

Mukai: No, not really. I’m not sure how the students at film schools or art universities make films nowadays, but in the film course at Osaka University of Arts then, our practice films and thesis films had to be completed on 16mm film. That cost at least one to two million yen. In order to amass that kind of money, we had to get all kinds of people on board. The film could not be made alone. The number of participants grew and staff roles were allocated – who does camera, who is good at loading the film stock, who can handle the equipment, and so on. It was different from the way you do things today, I guess. How does it work now?

Nishiguchi: It’s all digital and you get to handle film stock only until the second year.

Mukai: Ah, but you still get to work with film.

―With digital media which can be managed by fewer people, there is no need for a big crew anymore, right?

Nishiguchi: But we still need extras.

Mukai: I thought so. That seemed to be a lot of work. Did you have someone to coordinate that for you?

Nishiguchi: There wasn’t, so I had to resort to adding people to the university LINE group and calling out to everyone by messaging them “Please come.”

Mukai: The era of social messaging.

―Mr. Mukai, would you like to comment or give advice on Mr. Nishiguchi’s script?

Mukai: I feel that the directing and scriptwriting are on the same page and not in conflict with each other. The two boys in the opening scenes, especially the lines spoken by the boy with glasses. The way he says those lines in a somewhat comical manner allows us to recognize “aha, so that’s the cosmology of this film,” and accept it. It was all in the way he spoke the lines.

I really liked the seaside scene (where the protagonist and Sumire converse) – that was a major sequence, wasn’t it. The hero chases the girl and says, “Look, you’re wet.” – it made me go “What?” and I have to admit I laughed. It was visually just hilarious. And the word-play with “stand firmly” and “erection” was great. That was another gratifying moment.

But for the last scene where the protagonist’s line is obviously meant to lead Sumire to say “I’m wet now.” – that didn’t work and made me as a spectator wonder if there couldn’t have been a better way.

Also, you could have done better with the dialogue between the hero and the mother. “Show me your naked body,” is okay but the conversation leading to that makes them look more like siblings and not like mother – son.

―The structure of the screenplay is quite simple and conventional, isn’t it?

Mukai: This kind of film is actually quite tricky – you could either go the main golden road or try too hard and overdo it. Going straight down the highway is actually harder than trying something eccentric. So I was wondering as I watched the film, why this film “ED” lets manages to do it so straight and down the well-trod royal road. I’m still thinking about this question. Because the balance is just right. It’s connected to the dialogue I was talking about earlier. It’s like… not soiled or dishonest. It doesn’t look shamefully premeditated.

―The basic structure is solid, isn’t it? It’s about a problem and how to solve it.

Mukai: Also, there’s the girl who comes back and goes out. The time frame is set. I guess that’s why it works.

―Were you square about going for the main road, Mr. Nishiguchi?

Nishiguchi: Yes, I wanted to depict an ordinary love story, a youth story. It made it through the Yubari International Fantastic Film Festival selection, but I didn’t intend it to be a fantasy type – rather a serious take on an ordinary romance.

―After the prizewinning “Hazy Life”, director Nobuhiro Yamashita went on to become a solid commercial filmmaker. Mr. Mukai, do you have any idea why it worked for him?

Mukai: We made “Hazy Life” as a graduation film and won in Yubari’s Fantastic Off Theater Competition section. Luckily then we got a grant from the Tokyo International Foundation for Promotion of Screen Image Culture and made “No One’s Ark” (2002, dir: Nobuhiro Yamashita, script: Kosuke Mukai, Nobuhiro Yamashita) with it. Adding the subsidy from the Agency of Cultural Affairs, we were able to make the film on a 20-million-yen budget. So you could say we were lucky.

―Was the Yubari prize an asset to getting the production funding together?

Mukai: Yes, I think so. That foundation gave funding to one filmmaker per year in those days. Yamashita was lucky to be chosen. But he was still an amateur filmmaker then – directing films was not a sustainable profession yet. It took about another five years before he could make a living. So I do think that you (Mr. Nishiguchi) should go on and take any commercial opportunity of any genre that comes your way, however small it is.

―Without being prejudiced, you mean?

Mukai: There are many life choices. Some filmmakers will only work on original scripts, while others choose the road of being a commercial film director by taking on a variety of genres and trying to define themselves through that. Whichever road you take, there is no right or wrong. And I think there are more options today than ever before, in terms of lifestyles.

The main thing is the desire to create. I’d hope that you (Mr. Nishiguchi) will next try your hand at a feature length film. Once you experience a film longer than 60 minutes, you’ll see how the script and story establishes itself as something different. It’s not easy, but I think you can do it.

―Are you going to aim to be a film director, Mr. Nishiguchi?

Nishiguchi: The Yubari prize money is 500,000 yen so I guess I’ll just have to shoot another independent film with it, saying “hope it works out somehow.” I’m working on a script now, which looks to become a 90-minute film. I’ll take Mr. Mukai’s words to heart.

Mukai: Right, 90 minutes is good. Movies should be 90 minutes long.

Nishiguchi: Thank you so much.

Moderator: Naoki Motomura

Translator: Asako Fujioka

January 27, 2019 at B1 Theatre, National Film Archive of Japan

For information of the film and the director, please visit here.

―As a way of introducing yourself, tell us how you came to make “Orphans' Blues”.

Kudo: I’m Riho Kudo, director of the film. Thank you all for coming to see the film today. This is a graduation project of Kyoto University of Art and Design. I had always wanted to make a road movie for my graduation film. As the backbone of this film about a journey, I decided to use the motif of memory as a way of presenting the characters.

―Mr. Koji Fukada, how did you find this film?

Fukada: Hello, I’m Koji Fukada, film director. Seeing this film today for the first time, I found some things leave a strong impression. First of all, it’s not a conventional drama in the genre sense, and there’s a lot you don’t really understand at first glance, but you can feel there’s a strong awareness of light and sound. That’s why you can stay with it even if the story is hard to follow.

It’s the use of light in particular, for example where you have the torch light during the blackout and when rainbow-colored light streams in through the window. Many such scenes evoked the primitive joy of cinema in me. I can see your care for these things, and that you spent time and effort on these things during the filming. And not only light, but sound too. The sounds of construction work in the background, or the sound of rewinding tape – rare nowadays! –The film properly took into account these kinds of simple but delightful sounds.

As for the story, it’s a really mysterious story – kind of hazy, but then you notice more and more people, and the house is full of people, but you can’t figure out what their relation is to each other. At first we don’t know what happened in the past, but then you realize that the protagonist Emma is losing her memory, so you start enjoying this strange feeling that maybe the screen is presenting the world as Emma sees it.

Kudo: Premiering at Pia Film Festival, the film has gone on to show at several festivals, but I often heard from audiences that it is “hard to understand.” It’s a good lesson for me, but in fact I intentionally avoided exposition because I wanted suspense to be a part of the film. Like the scary scene of the mistress of the lodge washing dishes loudly.

Fukada: That scene was really loud. “Is the splashing sound of washing dishes really that loud?” I asked myself. You can’t hear it much from the hallway, but when Emma looks in the room, the sound jumps.

Kudo: In “Harmonium” (2016, dir: Koji Fukada), we see the wife character fervently washing her hands eight years later. That was such amazingly scary scene, it was a good reference for me. You want the audience to imagine why and build up the story in their heads.

Fukada: Thank you. This is a difficult thing, isn’t it? Making movies is always a tug-of-war with the imagination of the viewer. You let the audience imagine something, then you betray their expectations a bit, or you let the movie follow their imagination and let them “feel good,” and then you let them down, “aha, so that’s it!” and so on, playing them as you make the film. Mainstream entertainment movies and genre films are made so that the audience’s imagination doesn’t fluctuate that wildly and they are gratified easily. But with this kind of story, you are really cutting the edge so some people might get completely lost.

This is my personal reflection – since I watched it with the understanding that it’s the world view of a girl who’s losing her memory, by the end of the film it didn’t matter whether the guy at the end was Yan or Ban – the unraveling allowed me to let go of that.

Kudo: Thank you.

Fukada: Also, about the sound. I liked how the moment the lodge owner entered the image, the sound of dishes being washed suddenly gets louder. It’s as if Emma’s vision is connected to her ears. There were some other instances of sound usage that were unusual.

One time in the first half, the camera is filming the living room from outside and the characters are all indoors. Normally you would think that since the camera is outdoors, you’d hear the sound of chirping insects loudly and the dialogue not so much. But in this film, we hear the insects loudly when Emma opens the window from inside. So the camera is on the outside but the subject who’s hearing sound is indoors. That was a bizarre thing to do. Sorry if I’ve got it wrong. But I felt the film is really “nicely odd” in that strange shot, the use of light as I said before, and the use of sound.

Kudo: Regarding the shot of the lodge from outdoors – I wanted to show them in the living room from an overviewing position, then to get closer to them when Emma opens the window. That kind of feeling. So I deleted the sound recorded before that moment, like Ban’s voice, and designed the sound so that we get closer to them when she opens the window.

Also, when Emma passes by the man who looks like Yan in the market, the drums get louder. The sound person proposed this idea to me and I said “Yes, that’s a good idea.” I’m actually quite fond of that scene. What did you think?

Fukada: I do remember the sound for that scene. But I didn’t really get who it was she bumped into. So I glided through it without really thinking. Where do we see Yan for the first time?

Kudo: He first appears in Emma’s dream.

Fukada: In that dream series, you hear the whistling of the boiling kettle, and then as the finger closes in on the skin, the whistling gets louder. That was really good direction, I thought. The kettle sound and the drums tell us that Ms. Kudo, your attentiveness to sound and light is enough to sustain the film. By the way, where did you shoot this film?

Kudo: We went to something like seven prefectures. In the Kansai area, it was Kyoto and the neighboring Osaka and Kobe, but we also travelled far, to places in Shikoku region for the factory scene. Initially we wanted to go to Okinawa, but lacked funds.

Fukada: Wow, amazing that you were able to shoot that atmosphere so much like Okinawa. Just with Ban’s aloha shirt we believed it. There was also something China-like, wasn’t there.

Kudo: Yes, that was Kobe's Chinatown.

Fukada: I see. I kept wondering throughout the film, “Where are we now, what kind of world is this?” It was like a dream world. “It’s like fragments of memory,” I thought as I watched it. So that was all Japan?!

I was surprised to hear that you (director Kudo) wanted to make a road movie. It didn’t feel much like we were traveling. More like drama in a closed chamber – at least, the scenes in the lodge left a strong impression. The secrets between people and a closed community gradually are revealed…? Or maybe not really. But I thought there was something other than a road movie that the director was aiming for.

The other thing I noticed are the names. Ban and Emma. They don’t sound very Japanese. This is one of the reasons the film seems to have no nationality. Did you intentionally choose un-Japanese sounding names?

Kudo: Yes. Ban comes from the French word for wind – vent. The characters in this film are inspired by French language. In French, nouns have female and male genders. Wind is male, ocean is female, summer is male, and so forth. Emma embodies the sea. She derives from the ocean, while Ban is the name given to the man. I chose the name Emma from a character of a favorite film “Blue Is the Warmest Colour” (2013, dir. Abdellatif Kechiche). It’s the role Léa Seydoux played. I decided that for this film, I won’t use Japanese-ish names.

―Ms. Kudo, is there anything you want to ask Mr. Fukada?

Kudo: I was very particular about the wardrobe in this film. I found red-colored clothing to be very effective in “Harmonium”. I was really moved when a red shirt appeared under the white overalls. So I wanted to utilize colors in my film too. For example, Ban’s girlfriend Yuri doesn’t wear cold-colored clothing until she fights with Emma. Then she wears blue in the fight scene. In contrast, Emma wears cold colors throughout the film. That was my intention, but what did you think?

Fukada: It left an impression. I noticed that you were probably choosing colors intentionally after much thought. The greenery and the blue of the sea, and the colors of the clothing of the character standing there. As for what you did with cold colors and the flow of the story, I guess that kind of thing would be registered in the viewer unconsciously. But I did understand that the costumes were chosen for their colors.

Talking about wardrobe, you might remember that Tadanobu Asano wore red in “Harmonium”. He appears in the first half and disappears in the middle, so by leaving the strong red impression of him, I thought that the audience would be reminded of him every time they see red thereafter. So I flashed bright red clothing in the strongest scene.

I like to see how things change due to wardrobe color. But getting the balance right is not easy. In a naturalistic visual style, using color intentionally can feel very manipulative and could stick out like a nail. I am always concerned about the balance in such cases when I do my own films.

―Ms. Kudo, are you aiming to become a commercial film director? Will you continue doing independent films, or are you interested in working as an assistant director? There are so many choices. Do you have a specific plan?

Kudo: I do want to direct. As long as I have ideas which I want to turn into film, my aim will be to be a director. I’m not saying once I’ve become my own director I won’t assist again – I’d like to keep doing both. I do take on assistant director roles on my friends’ films, and I would love to keep making my own as well.

―Mr. Fukada, do you have any advice for her?

Fukada: This is something I often say strongly to young directors. If you are not aspiring to be a commercial film director in the program picture vein, and hope, however slowly, to pursue projects that you yourself want to make, you should know that you will not be able to keep making films with your chums in the way you did your graduation film. Sustainability is a problem. In Japanese society, labor conditions are not strictly regulated and so in fact people do make films without consideration for the work force (as in low pay). But in order to continue making the films you want, over a long period of time, I do think you need to think about proactively raising funds to make your project come true. Japanese film schools don’t teach you anything about money, so you should think about this.

Kudo: Thank you.

Moderator: Naoki Motomura

Translator: Asako Fujioka

January 27, 2019 at B1 Theatre, National Film Archive of Japan

For information of the film and the director, please visit here.

―As a way of introducing yourself, tell us how you came to make “CenterLine”.

Shimomukai: Thank you all for coming today. I’m Takumi Shimomukai, the director of “CenterLine”. Here (on my lap) is the artificial intelligence robot MACO2 who "acted" in the film.

I currently work as a company employee in Matsumoto, Nagano Prefecture. I had been making films since university days, and wanted to continue filmmaking alongside my job. I like mainstream commercial films, especially detective dramas and sci-fi, so that’s the kind of film I aspired to make, although maybe you generally wouldn’t call them independent films.

―When we asked Mr. Shimomukai which film professional he wanted to seek advice from, he proposed Takashi Yamazaki. Mr. Yamazaki, what did you think of his film?

Yamazaki: I was amazed that he is aiming for authentic entertainment as an indie. Independent filmmakers often get intellectual, making films that scream “this is what indies are supposed to be.” I have an affinity with people who make films like yours, and I like your stoic stance of defiance. Seeing how you took artificial intelligence (AI), a very interesting and contemporary subject, and delved deeply into its core, I was pretty impressed.

MACO2 is similar to Righty (the character in “Parasyte: Part 1” (2014, dir: Takashi Yamazaki), isn’t it? We spent a lot of money building Righty, but MACO2 consists of radio-controlled motors. Even though it’s a simple structure, you make it look like an AI device and you aren’t afraid of dealing with AI technology. Independent filmmakers usually avoid things like robot vacuum cleaners, even. But you put effort in filming these things properly and that attitude is definitely positive for me. MACO2 runs on remote control and has just two servomotors. It’s cheap.

Shimomukai: It was a challenge to fully express emotion while minimizing the number of moving parts.

Yamazaki: I’m jealous that you’ve done it so well (laughter). Its dialogue is monotone and dry, and motion is limited. And yet by the end of the film you find yourself sympathizing with MACO2. The great achievement of this film is how it reaches the point of recognizing the robot: “Hey, you have emotions!”

―It must have been hard to create the world of the near future.

Shimomukai: My concept was not to recreate the popular image of “flying cars” or “high rise buildings” but to convey a realistic future that is an extension of today, like “10 years from now.” I wanted to counter-balance the shocking and preposterous image of a physical robot (MACO2) testifying in court, by presenting the other scenes as realistic to us today.

Yamazaki: That “future is an extension of today” – it worked. We tend to imagine a future departed from our present, but you chose to present a near future maybe three or four years from now.

Your main issue was whether AI has or will give rise to emotions. That’s a really interesting take, but at the same time I questioned why you set up the main character as a prosecutor. If you wanted to make an ordinary buddy-movie, you could think of an apathetic freshman lawyer who transforms through meeting with AI, tries to protect the robot but is discouraged because she can’t, and has to say goodbye… But in your case it gets complicated because she’s a prosecutor. She has a role to (convict him and) solve the case, while at the same time a buddy friendship evolves. So tell me about this.

Shimomukai: As we saw in “Parasyte: Part 2”, the buddy genre states that “the film concludes with farewell.” So that was at the basis of my choice to set prosecutor against defendant.

Yamazaki: AI-themed films often veer towards grand issues like singularity (the turning point where AI surpasses human intelligence). But this film is a smaller story and this size is really great. It is closer to home, and the emotions are personable and easy to empathize with. If you set up a drama with a huge conspiracy lurking in the backdrop, it becomes a more distant story. It obviously would not fit the budget and the grandness would just look fake. Meanwhile, this story deals with whether AI can feel or not, and whether we can call it emotions. That lends itself to a terribly fundamental drama and is in fact a huge topic.

AI stories are fun. I’ve always wanted to try my hand at it and have kept thinking about it. Now I see this is one way to deal with the issues. But I still think she should have been a lawyer. I understand why you would want to take the strong emotional tie in your direction, but did you ever think of a defense lawyer?

Shimomukai: I didn’t.

Yamazaki: Hmmm. I envisioned the film with the lawyer and it made me cry.

Shimomukai: Did it really?

Yamazaki: Yes. A lawyer story would work. Two people in a conflict form an inseparable bond, but then the verdict is passed and they are torn apart. And the AI robot really had emotions. That seems like a pretty good story. It’s of course the director’s decision what ending you choose. But I do think a lawyer version could have worked, too.

I also thought the way the story ended could have been simpler, especially for the protagonist’s emotions. The audience was not sure what to relate to for some time. Maybe some would say that (what you did) is a cinematic device, but I think entertainment needs a very simple and understandable storyline. For example, in “Midnight Run” (1988, dir: Martin Brest) it’s a cop and an accountant. How these two conflicting characters develop a friendship – that’s the essence of the buddy story. That’s why the plausible couple in this case would have been “the lawyer and the criminal robot.” That’s the royal road to success, and with those contemporary elements I would think this could have been a great story. Another shot at it.

That she believes that the AI has feelings etc… that would have struck emotional chords.

Shimomukai: This may sound like an excuse, but there was also the problem of locations. A defense lawyer would meet with the defendant in a special meeting room. We didn’t have access to such a shooting location. If it were a prosecutor, she could meet the accused in her office. The office space could be pretty much anything in a fiction context, so we were able to use the warehouse in this film. So the production limitation was one of the reasons.

―Mr. Shimomukai, do you have anything you’d like to ask Mr. Yamazaki?

Shimomukai: I never thought building the story around the defense lawyer could be the better option, but I was concerned about making the film understandable, in order for it to work as an entertainment piece. The initial idea was to use non-stop dialogue, like in “The Social Network” (2010, dir. David Fincher). But because of the speed of dialogue, some viewers told me “the lines were a bit too fast.” I realized that the balance between concept and understandability is tricky. Mr. Yamazaki, you mentioned now that films should be made accessible. Can you tell me more about your take on creating entertainment?

Yamazaki: I think it’s always important to make clear where the viewers place their emotions. Of course, you could have some extra leeway or some cinematic complexity, but in general it is better to draw the emotional curve as an obvious and distinct arc.

In that sense, I think that your protagonist’s stance is a bit too complicated. I’m being repetitive here, but I don’t know how a prosecutor can form a buddy partnership with the robot. She’s helped by him, and some kind of friendship blossoms, she realizes that the robot has emotions and they go to a deep place. But in court, she seemed so eager to pass sentence on him.

Normally, if you became attached to the robot, you would be hesitant about convicting him. But her acting made her seem like she was rarin’ to go (laughter). Rather than “I sympathize with him, but I have to do it,” it looked like she was more concerned about her pride and status. So with this ending, I feel that you lose sight of the main points. You have to draw that natural arc of emotion. I think it would have been easier if she were a defense lawyer.

―Mr. Shimomukai, you made this film while working full time as a company employee, right? How did you manage to lead the production? What will you do next?

Shimomukai: After work I get home around 10 pm and then I work on the script and write emails and communicate with others. That was my life for around half a year. The filming was during the Golden Week holidays, so it was easier to get leave.

I think it would be pretty tough to leave my job and become a fulltime filmmaker. I hope to keep making entertaining movies while leading this same lifestyle. But maybe we can wish that the remake rights to “CenterLine” sell to Hollywood, and ten years later someone says “For this project we need a Japanese filmmaker’s sensibility,” and brings it back to Japan, where Mr. Yamazaki directs the version with the lawyer as protagonist…? (laughter)

Yamazaki: Me? I’m making the lawyer version? (laughter)

Shimomukai: I’m kidding of course, but I hear some people calling for a sequel to “CenterLine”. I wonder whether or not an exciting series could come out from this idea. I also like musicals, so I hope to keep trying my hand with other genres, too.

―Do you have any advice for Mr. Shimomukai, so that he can keep climbing the ladder?

Yamazaki: It’s not often that an indie filmmaker aims for the entertainment market. Maybe there are more now than before. Since “One Cut of the Dead” (2018, dir: Shinichirou Ueda), we are seeing more. Why not follow the success of “One Cut of the Dead”?

In the Japanese film world, intellectual styles are respected and art films are considered one rank higher. But I think good entertainment has to be sustained, or else the entire industry will shrink. I really think that kind of (entertainment) filmmaking should continue because an increase of such filmmakers with aspiration will benefit Japanese cinema. I’m personally pleased for entertainment filmmaking to grow. The more presence they show in the independent scene, the higher the possibility for the next “One Cut of the Dead” success, no kidding. Whatever the cinephiles tell you, just barge ahead with what you believe is entertainment.

* This text has been edited to avoid spoilers.

Moderator: Naoki Motomura

Translator: Asako Fujioka

January 27, 2019 at B1 Theatre, National Film Archive of Japan

For information of the film and the director, please visit here.

―As a way of introducing yourself, tell us how you came to make this film.

Fukuda: At the TOHO GAKUEN Film Techniques Training College where I was enrolled, all eighty students of my grade had to submit plot proposals. My own proposal didn’t make it in, but “Chonticha at end of the summer” was selected. It was Chonticha Takahashi’s film proposal, but she didn’t want to direct it herself, though she eventually became the film’s DOP. That’s how the role of scriptwriter and director came my way, and I directed the film.

―Isao Yukisada, also an alumni of TOHO GAKUEN is joining us here on stage. Mr. Yukisada, how did you view this film?

Yukisada: I’m of a different generation, but I’m very pleased to see female filmmakers like (Ms. Fukuda and) Aya Igashi emerging from the TOHO GAKUEN program. This film is my type of story – when I made the film “Go” (2001, dir: Isao Yukisada), I also thought deeply about similar issues like what’s in a name, or what does nationality mean. We are all bound by various things, including our names – something very symbolic. This film deals with this. It’s about a girl named Chonticha who, being not Thai, Myanmarese, nor Japanese, finds herself in a somewhat drifting uprooted place. It’s not easy to express that in a film, but I felt it carry across to me directly and in a simple way. I found that to be the strength of this film.

There were some shots that I especially liked. It’s a sincere film, I felt. It even chooses not to use any music. You would think that using music on the end roll would make it look better, but the filmmakers chose to end it like that (without music). By eliminating music, that invisible thing called identity is highlighted in relief. With a score, the film would have descended into an over-the-top sentimentalism, so I appreciate the filmmakers’ attitude in avoiding the trap and allowing for the essence to come across strong and clear “as it is”.

―Ms. Fukuda, did you at any point think about using music?

Fukuda: I’d thought that using music for a 40-minute film, and especially a straightforward film like this would be difficult. At first, I tried it out but whatever score I used, there was an overwhelming sense of doom that prevailed. Obviously, the subject matter is not a light one, but it was as if the harder I tried, I got locked into a stereotype. That dilemma was also always on my mind when I was writing the script. The plot centers around a girl caught in unhappy circumstances, but I questioned whether an audience would really like to see the sympathy-drenched depiction of a social issue. I decided to go against that. This became the approach that drove the script, the protagonist’s character, and the choices regarding music.

―Is the story based on the real experiences of your friend Chonticha?

Fukuda: The early stage of the plot stated that Chonticha Takahashi had parents who were Myanmarese and Thai, that her mother ate cicadas, and that her Japanese father was a bother. I used these elements as the backdrop of her life and concocted the rest in order to carry the story. I added the boy character Futa to make the narrative understandable.

Yukisada: It’s set up as a love story, isn’t it? Futa’s line “I like the name Chonticha,” helps the audience in our understanding of the film. Chonticha probably thought deeply about her name because of the pressure to become Japanese, but we don’t know if she liked it (initially) at all. But we can sense from how the script is written that (thanks to Futa’s comment) she comes to approve of it. I also think the actors in this film were great. The girl who played Chonticha is actually Japanese, isn’t she?

Fukuda: Yes. It was love at first sight for me, with the girl who played lead, Lynn Nagatsuki. After I fell in love and started talking to her with casting in mind, I found that she had spent five years in America and three years in Thailand due to her parents’ work. She told me, “I can empathize with the role because there’s a part of me that can’t identify as a Japanese.” It gave me confidence that “This girl would be able to do it well.”

―The production is entirely staffed by students, right?

Fukuda: Yes, it’s a graduation thesis project.

Yukisada: The quality of the work is much higher than during my time. When I was in school, they gave us some money – “Here, make the thesis film with this.” But it was such a small amount. In my case, I broke lots of rules (in making my thesis film). First you submit a treatment, right? But I went on to write a screenplay that was totally different from the original proposal. It’s like the front and back sides of a surface – when I justified the difference by saying, “The story evolved as we were filming,” the school authorities got mad at me and cancelled the screening. There was content that was kind of sado-masochistic, and I used cicadas, too. It was a torture chamber, a woman was crucified in a room filled with live cicadas. We kept throwing cicadas into this shed, and they were singing so loud. I had my junior staff go capture more and more of the insects because cicadas don’t live very long. I pasted them onto the walls. That was my film.

Fukuda: I’d love to see it.

Yukisada: Me too, but apparently the school never kept a copy. I looked for it, but couldn’t find it. They really grilled me then: “Why did you make such a film, it’s awful.” They also told me “You’ll never become a pro” and “Obviously this can’t be broadcast.” At the time it was not a film school but a broadcasting course, and it was set up so that the graduation projects were to be shown on TV. “This film won’t pass the broadcast code (of censors) and won’t ever get broadcast,” they complained. We’d invited a stage actress to do the part, and her pubic hair was clearly on screen.

Fukuda: I’m envious. I have lots of complaints with the current system at the school. There are too many rules that keep you from filming what you want. It’s as if you have to follow the tracks already laid out for you, and you start wondering “is this really the film I wrote?” I do have respect (for the teachers) and I did learn a lot, but in terms of making your own thesis film, I feel that the school is infringing on our freedom.

―Is there anything you want to ask Mr. Yukisada?

Fukuda: Mr. Yukisada, how do you manage to keep making films? I’m sure there are times you don’t want to do it anymore.

Yukisada: Hmmm, let me see. Well, I have to make a living. I can’t do anything else. I tried my hand at theater, but that was because my film projects weren’t getting funded. I just went on doing stage after stage, and then suddenly the film industry people started saying, “Why are you doing theater?” and began to give me lots of film work.

Similar to how we are bound to our nationality or our names, films are also often stuck to titles and subject matters. But if you free your mind from such frameworks, it boils down to finding something valuable in every shot you film. The moment you are shooting it, you can forget everything else and it becomes easy. You just shoot what you have decided to shoot.

But it’s the hassle of what comes before and after the filming that I hate. “Will they understand?” When you find a great location and say, “This is where I want to shoot,” the next question is “Will we get permission to shoot here?” Mostly negative things come into the picture. When you’re writing a script, it’s “What will the author of the original story say?” or the producer will say, “That’s no good, change it like this,” and so on.

Those are the things I don’t like, but if you ignore that and consider filmmaking to be a series of shooting, one shot after the next with staunch determination, you can handle any subject matter. After 20 years of being a film director, you would think I’d be used to it by now – but in fact, not at all. For every film, I am reset to novice state. I am afraid. So I have to say, I am afraid, but I have no choice because this is all I can do. That’s how things are. Ms. Fukuda, you can still avoid that road. You can go live a normal life (outside filmmaking). –But then on the other hand, now with your award and all, and the fact that your film is being shown at the National Film Archive of Japan – none of my films have shown here – I guess it’s a big deal (laughter).

Fukuda: I’ll do my best.

Moderator: Naoki Motomura

Translator: Asako Fujioka